In the rainy season, the road through Bardo community in Jigawa State favors only bullock carts. They carry farm produce. They are also the only means of transporting ill persons and pregnant women from Bardo to Ajaaura Primary Health Care Centre, some 15 kilometers away.

Rahama Sabo and her husband, Sabo Sarkin, went on that journey from Bardo when she went into labor to give birth. They spent two and a half hours before they reached the Ajaaura Health Centre.

“The baby’s legs had already come out before we got to the hospital,” Sabo recalls of the journey with his wife in labor. “Blood was flowing to an extent that the clinic almost rejected us before we were eventually considered after narrating our ordeal. It was a futile effort because my wife and the baby died shortly after our arrival around 10 pm. This wouldn’t have happened if Bardo PHC, of 10 minutes trekable distance from my house was functional,” Sabo explains.

Yes, just a 10-minute walk from the Sabos is a newly painted health center in Bardo, Taura Local Government Area of Kano State. But it is not functional.

Bullock Cart in Bardo Community

Women Buy Fairly Used 'Ambulance' to Reduce Mortality Rate

For 10 years, the center has stood pretty as a physical structure, but it lacks manpower, furniture, and basic amenities to serve Bardo’s 10,000 population, says Saminu Usman. He is the In-charge of the facility and the lone worker running skeletal services for over 20 years in the area. Usman usually locks up the facility when he is on break or embarking on other official tasks. Umar Harisu, the community leader says Rahama’s death is the sixth maternal mortality on recent record in Bardo, directly related to the unserviceable primary health care center.

With the center being nonfunctional, women in the community devised a means of taking the 15-kilometer journey to Ajaaura. “To avert recurrence, some community women recently contributed N1,000 each and bought a fairly used car to be conveying their fellow pregnant women to Ajaaura PHC,” says Harisu. The state government did not bother making the Bardo PHC functional. Instead, it provided a defective ambulance to complement the women’s car.

The car bought by the women and the ambulance provided by the state government

Bardo PHC is not alone. Many primary health facilities in the state lack manpower. They rely heavily on voluntary and casual workers, as well as other ad-hoc staff temporarily engaged by international donors or nongovernment organizations. One of such projects being implemented by the Global Alliance for Vaccines Initiative hired Yasin Nafisa, who is the only midwife at Garin Ciroma PHC. Over at Yalawa PHC, the only midwife is also employed by the same project. She is from Niger State. Twice a year, she gets a cumulative period of three months of annual leave, with nobody to replace her.

“I will be here for three years for GAVI project’s lifespan. I usually make sure that my leave does not clash with my colleague at Yalawa PHC so that we don’t leave the entire community in danger,” she says. Also, at the Yalawa PHC, the only available midwife was engaged by the GAVI project as confirmed by Hashim Usman, the deputy In-charge of the facility.

Top Health Workers Get N10,000 Stipend Monthly

The situation is similar at Kiri PHC. Kamisu Yahaya was only recently engaged as a casual worker and put on a N10,000 monthly stipend after working at the center for four years without pay. He is now the deputy In-charge. “The only government worker here is the In-charge,” Yahaya says. “Even me, I just started collecting N10,000 monthly from money we are realizing from our patients. Other voluntary workers do not receive a dime.” This explains the awful situation of the PHCs in Nigeria’s northwest. But the states in the other five geopolitical zones are no different.

Northeast Nigeria Suffers Similar Fate

As it is in Bardo, Jigawa State; so it is in Malamari, Borno State. For several years, Malamar – just 10 kilometers from the state capital Maiduguri – did not have a PHC. Three years ago, one was built, but it has zero infrastructure. It has remained under lock for years, even as maternal and child mortality has risen 30 percent in the village.

Malamari PHC Under Lock

“There have been cases of death because most of the villagers are not financially buoyant enough to access healthcare in the city,” says Bulama Abba, the village head. Awana was a victim months ago, after a bout with malaria. His grandmother Zainab Musa recalls the night she lost her grandson. “His malaria illness became worse at night, and we didn’t have the transport means to take him to the city,” she says. “He was declared dead on arrival at the Borno Specialist Hospital the following morning.”

Zainab Musa

The transportation and financial challenges are daunting for Malamari, but the community is also besieged by the insecurity in Borno State, brought on by Boko Haram. “There is a midnight curfew. So, without a security escort, nobody would be allowed to visit the nearest hospitals,” says Bukar Tela, the chairman of the Civilian Joint Task Force in Malamari. The force provides security in the area.

Husband Helps Pregnant Wife Deliver at Home

Against the odds, some women in Waddiya community in Mafa Local Government Area of Borno State have resigned to fate by opting to give birth at home. The only PHC in the community is under lock due to inadequate manpower. Falmata Umar is one of the women who had no choice but to give birth at home, with the support of her husband. She holds her healthy infant in her arms as she tells her story. “I was supported by my husband to give birth to this baby at home just like other women in this village are doing because our hospital is not working,” Umar says.

Waddiya PHC

Niger State, in the Northcentral region of Nigeria, is not immune to the numerous challenges bedeviling PHCs across the country. For several years, residents of Ashuwa traveled 20 kilometers to Yangalu just to access medical care. In 2012, the state government built a PHC to end their plight. Five years later, the joy disappeared as the center fell into decay, says Usman Galadima, the community’s leader. “We rely on self-medication and there is no antenatal care for our pregnant women. They mostly deliver at home because our road is not motorable,” he laments.

Ashuwa PHC

Health Workers Abandon Ramshackle Facility, Render Home Services

Elsewhere in Mashegu LGA of Niger State is the Karamin Rami PHC. The facility is in growing deterioration. Health workers posted there have no place to work. Muhammed Babagi, the officer in charge of the facility says the dilapidated PHC has relegated them to treating patients at home on invitation.

Patients' Relatives Fetch Stream Water for PHC Use

Like in the North, PHCs in Southern Nigeria bear the brunt of daunting challenges. Failing structures, bat infestation, inadequate manpower, and lack of basic amenities are major challenges of the PHCs in Ogun State. Tonigbo PHC in Ijebu East LGA is in deplorable condition. It relies on rainwater for its water use. When the rains stop, health workers mandate patients’ relatives to fetch water from a stream three kilometers away before attending to their loved ones.

“We decided that relatives of our patients, especially pregnant women, should be fetching water from the stream because there is no potable water in the entire community,” says Oluwayemisi Igbosanu, the In-charge of Tonigbo PHC. Oluwatoyin Amusa, a farmer, was among the residents who recently fetched water before his pregnant wife gave birth to her baby at the facility. “If we don’t fetch water the delivery will be put on hold, it’s a normal practice here,” he says.

Bats Sack Patients and Health Workers

Many PHCs in Ogun State are battling bat infestation. Colonies of bats invading healthcare spaces have sacked patients and staff at the affected facilities including Ojelana, Atoyo, and Tonigbo PHCs in Ijebu East LGA. The bat feces litter corners, have damaged ceilings and rendered the health centers unusable.

Bat Feces Litter PHCs in Ogun State

The Ojelana facility – serving 41 communities and meant to operate 24 hours daily – is now a ghost of itself due to the unbearable odor of bat droppings and decayed infrastructure, according to Mrs. Bunmi Ibrahim, the only worker at the center. “We do take delivery here since the establishment of the center in 1981, but now we took only one delivery throughout last year [2023],” she says. The situation is bad, even patients desperately in labor do not want to stay. “Recently, a pregnant woman was brought here for delivery, and I allocated one of the rickety beds to her. I thereafter went out to get some delivery items but to my amazement, she sneaked out before I returned,” she explains.

Hold PHC Administrators Accountable, Government Official Says

In an official reaction, the Executive Secretary of Ogun Primary Health Care Development Board, Dr. Elijah Ogunsola, says the state government is currently renovating at least one PHC in each of the 236 political wards in the state. “We have renovated close to 100 now and it’s an ongoing project as some of them will be refurbished this January 2024, according to Dr. Ogunsola.

“On other challenges, you people [journalists] should help us hold the PHC administrators accountable, we pay them N100,000 monthly to run their activities apart from their internal income, so I wonder what they are using the money for if they don’t have water,” he said.

Oil-Rich Community Patronizes 'Mushroom Chemist' in Place of PHC

In the South-south geo-political zone, Umuechem Community in Etche Local Government Area of Rivers State lacks functional healthcare facilities despite their rich crude oil contribution to Nigeria’s economy. It has over 250 oil wells, but grass has taken over the vicinity of the only cottage hospital there and its roof was blown off in a windstorm.

Over in Orwu and Ogida communities, pregnant women depend solely on chemist shops for antenatal, delivery, and postpartum care due to the deplorable condition of the Orwu/Ogida PHC. Residents say there has been no replacement for several years since a midwife at the center retired and the building fell into decay. “Vaccinators are only using the facility during immunization exercise,” they complain.

At Obite PHC in Ogba/Egbema/Ndoni LGA, Synger Azubike, a resident said residents spend about N3,000 on transportation to access healthcare at the closest facility. Reacting, Kinikanwo Green, the Executive Secretary of the Rivers State Primary Health Care Management Board, admitted the outlined challenges. He said the board is working on general maintenance and renovation of the dilapidated PHCs and the employment of more health workers.

Pleasant-looking PHCs, Limited Workers and Amenities

In the Southeast, the aesthetics of buildings housing most of the 600 PHCs in Anambra are appreciably stunning. However, the PHCs also face inadequate health professionals and a lack of water and power supply.

PHCs in Anambra State

These challenges are well pronounced at the PHCs in Amanuke, Urum and Isuaniocha, all in Awka North LGA and Nteje PHC in Oyi, Ifitedunu PHC in Dunukofia and the PHC Abba in Njikoka LGA. Most of the PHCs have just about three workers – a staff on the government payroll and two volunteers – to cater to the entire community. They also lack isolation spaces to be used during outbreaks of contagious diseases.

Exorbitant Hospital Bills and High Drug Prices Put Patients Off

Some of the villagers also lamented the exorbitant charges and high prices of drugs at the facilities. The charges and prices are pushing pregnant women to patronize traditional birth attendants. A pharmacist, Uchem Chisom, the Executive Secretary of the Anambra State Primary Healthcare Development Agency admitted the challenges. He said the state plans to boost its health workforce by recruiting 500 workers for the PHCs, in addition to two medical doctors for each of the 21 LGAs in the state. Chisom blames the PHC authorities for the exorbitant charges and for sourcing drugs on the open market instead of utilizing the

Anambra State Central Drug Store.

Dead PHCs Force Patients' Influx to Tertiary Health Institutions

Tertiary health institutions are suffering the pinch of the struggling PHCs across the country. They are admitting about 60 percent of patients with minor ailments that should have been managed at the PHC level. Dr. Abdullahi Kabir Suleiman, the Deputy Chairman of the Medical Advisory Committee at the Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital (AKTH) confirmed that such an overwhelming influx is complicating their service delivery.

“We do receive about 50-60 percent cases that should have been handled by the PHCs but I will not blame the patients because they don’t get what they want at the PHCs,” he says. He is doubtful over the ability of the PHCs to withstand an outbreak of any serious disease such as Ebola or Cholera due to their deplorable conditions.

Eighty Percent of PHCs Nationwide Deplorable

Nigeria has some 34,076 PHCs. They account for 85.3 percent of the total hospitals and clinics in the country, yet the deplorable nature of most PHCs is subjecting rural dwellers to untold hardship. According to the Nigeria Health Sector Market Study Report, commissioned by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Nigeria (2022), about 80 percent of the 34,076 facilities are still non-functional. Consequently, the report, compiled by PharmAccess Foundation’s Nigeria Office (PAF), estimated that 2,300 children aged under five and 145 women of child-bearing age die daily.

State of Emergency

The different tiers of government are aware of these daunting challenges as evident in the 16 November 2023 declaration of an emergency in Nigeria’s health sector by the health minister, Prof. Ali Pate. Making the declaration at the 64th National Council on Health in Ekiti State, Pate said the nation’s health facilities were in bad shape, hence the need for urgent intervention.

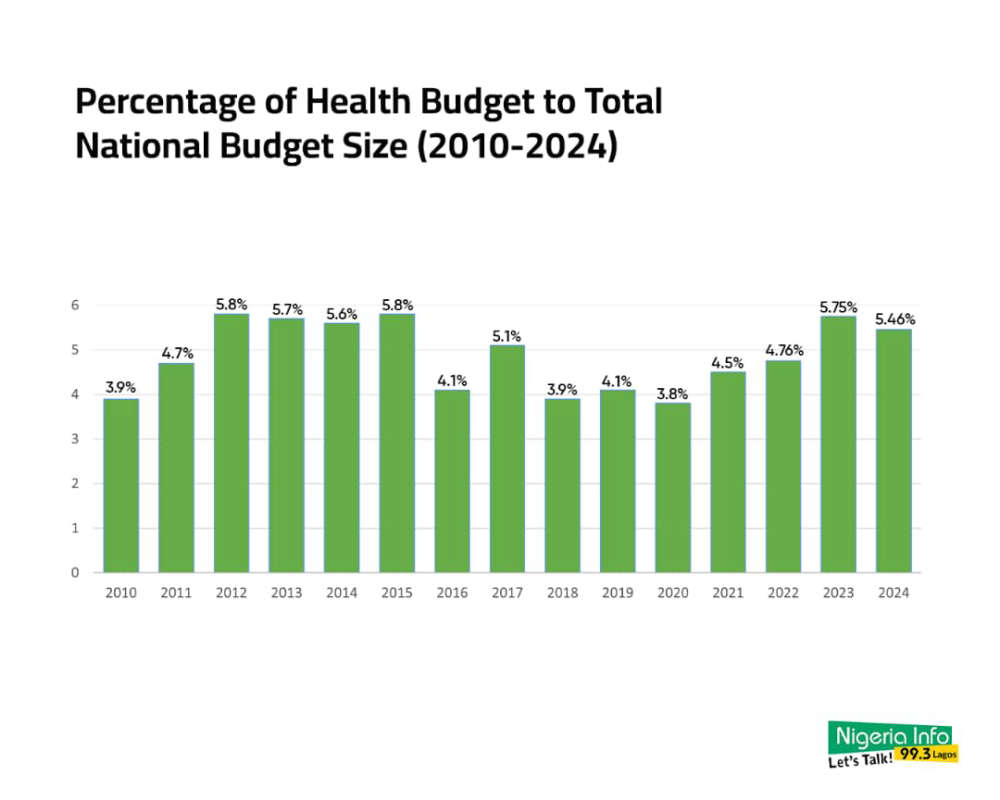

Despite the emergency declaration, an analysis of the 2024 budget allocation shows the allocation to the health sector still failed to meet the African Union target of 15 percent of the national budget.

The sector got the highest-ever annual budget allocation of N1.33 trillion in 2024, but the amount is only equivalent to 5.46 percent of the N28.7 trillion national spending plan. This is about one-third of the 15 percent Abuja Declaration Commitment, as 15 percent of the overall budget vote would have amounted to N4.125 trillion, leaving a funding gap of N2.622 trillion.

Federal Government Allays Fear Over Low Health Budget

Reacting in an exclusive interview with our correspondent, the Executive Director of the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency (NPHDA), Dr. Muyi Aina, said there was no cause for alarm regarding the low budgetary allocation. Dr. Aina, who assumed office in October 2023, admitted the aforementioned challenges but reeled out the long-term goals and strategies of the Bola Tinubu administration towards addressing the situation.

“There is a huge budget from the federal government, we also have Basic Health Care Provision Funds (BHCPF) which is 1 percent of the nation’s income and we do get substantial support from development partners which is not trivial,” Aina said. “So, what we are doing is to better harness the resources that the donors and partners are bringing to maximize the results.”

Shortly after the “state of emergency” declaration, the federal government launched the Nigeria Health Sector Renewal Investment Programme where the 36 state governors and development partners signed an agreement to ascertain results.

Government Plans to Upgrade One PHC Per Ward to Global Standard

There are over 8,000 political wards across Nigeria. Dr. Aina said the government is committed to the ongoing upgrade of one PHC per ward to a global standard and doubling the figure before the end of the administration’s four-year tenure. He also identified the production of frontline health workers and skilled birth attendants as one of the biggest limitations to scaling up PHC activities across the country. “The Federal Ministry of Health is making moves to overhaul the human resources for health supply for our PHCs workforce and midwives development program.

“We have begun the process of upscaling 120,000 frontline workers to have basic skills and they will be deployed to PHCs nationwide. There are several ongoing interventions that directly address the recent upsurge in the prices of medication and the government is pushing very aggressively toward local drug productions that can lower cost.”

When those conditions are in place, the PHC in Bardo would hopefully not simply be newly painted but would be able to save the lives of people like Rahama and her baby.